The Apolytikion of the Meeting of the Lord with the Elder Symeon in the Temple

The feast of the Meeting of the Lord with the Elder Symeon occurs on February 2nd, about halfway between Christmas and Pascha. We celebrate the day when Mary and Joseph brought the Christ Child to the Temple to fulfill two commandments of the Law: the purification of the mother from the flow of blood from giving birth (Leviticus 12:1-8); and the “buying back” of the first born male from God (Exodus 13:11-16).

Greek Text

Χαῖρε κεχαριτωμένη Θεοτόκε Παρθένε,

ἐκ σοῦ γὰρ ἀνέτειλεν ὁ Ἥλιος τῆς δικαιοσύνης,

Χριστὸς ὁ Θεὸς ἡμῶν, φωτίζων τοὺς ἐν σκότει.

Εὐφραίνου καὶ σὺ Πρεσβύτα δίκαιε,

δεξάμενος ἐν ἀγκάλαις τὸν ἐλευθερωτὴν τῶν ψυχῶν ἡμῶν,

χαριζόμενον ἡμῖν καὶ τὴν Ἀνάστασιν.

English Transliteration

Chere kecharitomeni Theotoke Parthene,

ek sou gar anetilen o Ilios tis dikeosynis,

Christos o Theos imon, photizon tous en skoti.

Efphrenou ke si Presvita dikee,

dexamenos en angales ton eleftherotin ton psychon imon,

charizomenon imin ke tin Anastasin.

English Translation

Rejoice full of grace Theotokos Virgin,

For from you arose the Sun of Righteousness,

Christ our God, enlightening those in darkness.

Rejoice also, righteous Elder,

having received in your arms the Liberator of our souls,

who grants us also the Resurrection.

The Hymn Sung in Greek and in English

A Dance Around Christ

The hymn, as is typical of many hymns, falls into two parts. Each part looks at a main character of the story, and directs the characters to the overarching main character, Christ.

The first part addresses the Thetokos, the second the Elder Symeon. Each is given a command to rejoice.

Chere kecharitomeni Theotoke Parthene

Efphrenou ke si Presvita dikee

They are then given the reason for this: the Theotokos has given birth to Christ; Symeon has received the Christ child in his arms.

The third line then applies a participle to Christ, attributing an aspect of our Salvation to the particular description of Christ.

- In the first part, Christ is addressed as the Sun of Righteousness. His action is to enlighten those in darkness.

- In the second part, Christ is called the Liberator of our souls. His action is to grant the Resurrection, the ultimate liberation from sin and death.

From Christmas to Pascha and Back

Since this feast fall roughly midway between Christmas and Pascha, it looks in both directions, thereby joining the themes of the two feasts together. In order to express this aspect of the feast, the Apolytikion uses language which captures all the highlights of the various feasts, melding them into one hymn.

The Previous Feasts

The first line:

Chere kecharitomeni Theotoke Parthene

is a variation on the greeting of the Angel Gabriel to Mary when he announced to her that she was chosen to be the mother of God (Luke 1:28).

Chere kecharitomeni, o Kyrios meta sou

Thus, the hymn begins at the beginning, at the Annunciation.

The second line:

ek sou gar aneteile o Ilios tis dikeosynis

mimics a line from the Apolytikion of the Nativity:

[tous magous] se proskynin ton Ilion tis dikeosynis

quickly moving from the Annunciation to the Birth of Christ.

The third line:

Christos o Theos imon, photizon tous en skotis

connects the hymn to the Feast of Lights, Theophany. In the Gospel for the Sunday after Theophany, we read how St. Matthew refers this prophecy of Isaiah to our Lord (Matthew 4:16):

O laos o kathimenos en skoti phos eiden mega, ke tis kathimenis en chora ke skia thanatou phos anetile aftis.

The people who were sitting in the shadow saw a great light, and upon those sitting in the land and the shadow of death a light has arisen.

The Future Feasts

The shift to the righteous Elder Symeon also shifts the perspective to the future, just as Symeon himself looks to the future of the child in his arms.

Symeon has received the liberator of our souls:

dexamenos en angales ton eleftherotin ton psychon imon.

The title eleftherotis is appropriate for our Lord’s death on the cross, since through His death He liberated us from sin and death.

Finally, through His conquest of death, Christ also grants to us the Resurrection, the promise of renewed life.

From Christmas and Pascha and Back…to Us

On this Feast Day, we too stand poised between Christmas and Pascha. Our hymn reminds us that we cannot separate the two events, that they are inextricably bound up with each other. Christmas can never be for the Orthodox Christian a warm cuddly feeling about a little child in a manger with cute little animals all around. Christmas must always point to God’s great sacrifice for us, it shows us the Child, not a sweet little boy, but as the Liberator of our souls. In the same way, the great acts of our salvation, our Lord’s Death and Resurrection, can never be separated from the initial sacrifice of the Son of God in becoming a human being, in taking on our human nature and living and sanctifying every aspect of our human lives. Very often in our “religious thought” we consider the only events of our Lord’s life to be Christmas and Pascha, and that these are two very distinct events. This Feast and its apolytikion remind us that these events frame a whole life and that they can never be separated but must be joined together into one whole continuum of salvation.

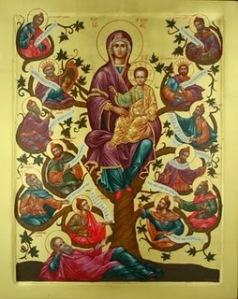

![Entrance of the Theotokos to the Temple[2]](https://photistos.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/entrance-of-the-theotokos-to-the-temple2.jpg?w=276&h=300)